What are Blebs?

Blebs are blister-like protrusions that occur at the cell surface (reviewed in [1]). Blebs form, and function, in a series of defined steps. They typically grow to a length of around 2 µm within 30 seconds, before shrinking back for another 120 seconds. Blebs are well known as a by-product of apoptotic and necrotic processes, even though they are not essential for the execution of either of these programs [2]. In recent decades, the role that blebs play in the locomotion of some cell types became increasingly acknowledged. For example, bleb-mediated cell motility was observed in early embryos and was termed amoeboid motility [3]. Blebbing (amoeboid motility) has been observed in studies of both unicellular [4][5] and multicellular systems [6]. The unicellular form of Dictyostelium discoideum takes the form of an elliptical cell, which moves through alternating cycles of expansion and contraction, coupled with low-affinity substrate binding. These are both characteristic features of blebbing motility.

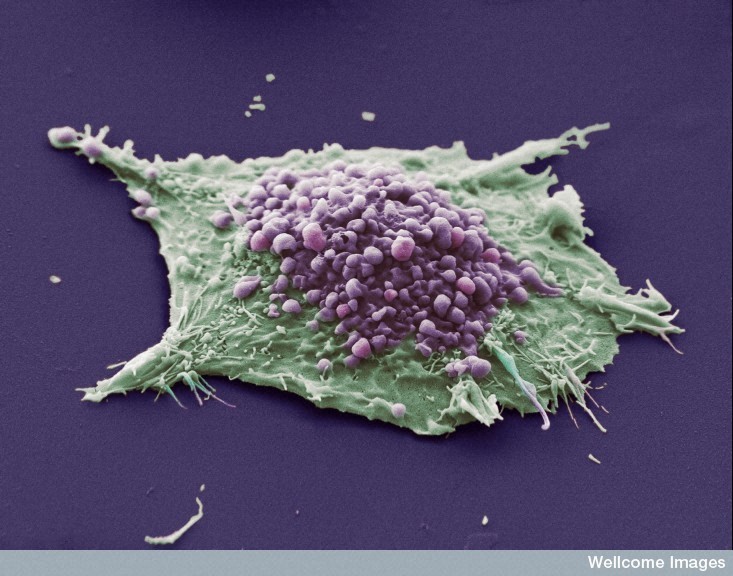

This scanning electron micrograph shows a single cell grown from a culture of lung epithelial carcinoma cells. The purple area shows blebs, which are irregular bulges in the plasma membrane of the cell caused by localized decoupling of the cytoskeleton from the plasma membrane. The green area shows an area of the cell where the blebbing is not occurring or is not visible. Image CIL:39108 is attributed to Anne Weston and used under Creative Commons Licence CC BY-NC-ND 3.0. Further information available at http://www.cellimagelibrary.org/images/39108

In multicellular eukaryotic systems, both leukocytes and certain tumor cells have been observed to move in an amoeboid fashion, distinct from that of mesenchymal migration [6]. These movements are generated by cortical actin and driven by weak and short-lived interactions with the substrate [7][8]. Some cancers preferentially use this type of motility to avoid the requirement for extracellular matrix (ECM) proteolysis [9] and escape tissue barriers [7].

Blebbing motility has also been observed in a variety of other cell types and model organisms, including fish embryonic cells [10][3], primordial germ cells (PGCs) in zebrafish [11] and Drosophila melanogaster embryos [12].

Although blebbing is now known to be a mode of migration, much of the initial findings on the mechanics of blebbing comes from non-migratory cells. Subsequent studies suggest similar mechanisms are likely to be used by migratory cells. In both cases, the blebbing cycle can be simplified into 3 major steps, namely initiation, expansion and retraction [1].

References

- Charras G, and Paluch E. Blebs lead the way: how to migrate without lamellipodia. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008; 9(9):730-6. [PMID: 18628785]

- Fackler OT, and Grosse R. Cell motility through plasma membrane blebbing. J. Cell Biol. 2008; 181(6):879-84. [PMID: 18541702]

- Wourms JP. The developmental biology of annual fishes. II. Naturally occurring dispersion and reaggregation of blastomers during the development of annual fish eggs. J. Exp. Zool. 1972; 182(2):169-200. [PMID: 5079084]

- Stockem W, Hoffmann HU, and Gawlitta W. Spatial organization and fine structure of the cortical filament layer in normal locomoting Amoeba proteus. Cell Tissue Res. 1982; 221(3):505-19. [PMID: 7198940]

- Pomorski P, Krzemiński P, Wasik A, Wierzbicka K, Barańska J, and Kłopocka W. Actin dynamics in Amoeba proteus motility. Protoplasma 2007; 231(1-2):31-41. [PMID: 17602277]

- Sahai E, Garcia-Medina R, Pouysségur J, and Vial E. Smurf1 regulates tumor cell plasticity and motility through degradation of RhoA leading to localized inhibition of contractility. J. Cell Biol. 2006; 176(1):35-42. [PMID: 17190792]

- Friedl P, and Wolf K. Tumour-cell invasion and migration: diversity and escape mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003; 3(5):362-74. [PMID: 12724734]

- Pinner S, and Sahai E. PDK1 regulates cancer cell motility by antagonising inhibition of ROCK1 by RhoE. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008; 10(2):127-37. [PMID: 18204440]

- Sahai E, and Marshall CJ. Differing modes of tumour cell invasion have distinct requirements for Rho/ROCK signalling and extracellular proteolysis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003; 5(8):711-9. [PMID: 12844144]

- Trinkaus JP. Surface activity and locomotion of Fundulus deep cells during blastula and gastrula stages. Dev. Biol. 1973; 30(1):69-103. [PMID: 4735370]

- Blaser H, Reichman-Fried M, Castanon I, Dumstrei K, Marlow FL, Kawakami K, Solnica-Krezel L, Heisenberg C, and Raz E. Migration of zebrafish primordial germ cells: a role for myosin contraction and cytoplasmic flow. Dev. Cell 2006; 11(5):613-27. [PMID: 17084355]

- Jaglarz MK, and Howard KR. The active migration of Drosophila primordial germ cells. Development 1995; 121(11):3495-503. [PMID: 8582264]